Digging in Yixing Part II

After much discussion, research and digging during a week spent in Yixing, it’s not difficult to see that the price of an Yixing teapot is made of at least 3 major factors:

Quality/Cost of clay + Labour/Workmanship + Reputation and Abstract add-ons = Price or Value (subjective)

Compared to reputation of the artist and aesthetic factors, which are highly subjective, you would think that the clay used should be a straightforward aspect to analyze. The cost to mine it, process it and scarcity should sets a price that is relatively easy to understand. Unfortunately, it’s not.

Although many teapot aficionados have their methods of determining authentic clay types, these are often flawed at best and don’t provide conclusive results on their own. Even among “experts”, conflicting opinions or facts will often arise. Many of these methods are originally perpetuated by sellers as sales tactics (similar to puer tea, ie- “thick stems = gushu”, not “thick stems = fertilizer”), but don’t necessarily hold weight. With enough repetition, the echo chamber that is the tea community amplifies these and people start finding reassurance by clinking the lid on the body and finding small grains in the clay.

We don’t want to sound too pessimistic here, but as sure as sellers and producers know these tricks and cues people rely on to determine authenticity, they’re also able to replicate them. This was evidenced to us in person. Some sellers openly indicated that they can produce teapots “according to the buyer’s needs”. Most makers have multiple clay sources that they use. This can help them produce pots of different quality or cost, which is understandable, but also imitate certain qualities or characteristics within a set price range if need be. Yet again, this is another similarity to puer, where certain processors will offer to employ processing tricks to enhance the immediate fragrance of puer, often at the risk of its ageing potential.

As we mentioned in our previous post, being in Yixing really feels like being in tea mountains sourcing puer. Most people you meet will tell you their pots are made from “original mine zini/zhuni/dahongpao” from Huanglongshan without hesitation. This is Yixing’s equivalent of the 1000 year old gushu. Not an exactly a mythic beast, but one that you have to see for yourself to truly believe. And one that you’re certainly not going to get a “deal” on.

It’s important to remember that most of these sellers have been doing this a while. The answer you will get to a question depends very much on your accent, where you’re from, how you look and what you seem to know – nevermind being a foreigner in China. We approached most people with the same set of standard questions and often got back the same dubious responses. When asked about claims or pressured with information like scarcity and cost, each seller usually just said it’s from their own store of old clay, which they could very likely have, but probably didn’t use on that $80 pot in your hands.

It was quite cold during our time in Yixing. This meant that a lot of shops in Dingshuzhen were closed or on strange hours, as people didn’t want to work when it’s too cold. This also reflects the demand for Yixing teapots domestically, which means people can more or less choose when they open shop, as business still comes to them whether the door is open or not. In the case of one “laoban” (boss) that we overheard, he was joking about an order he just received for 3.2 million teapots and that if he only makes ¥10RMB per teapot, that’s still ¥32 million. Just remember that next time you’re browsing $40 “zisha” on eBay or Aliexpress.

While in search of some late-night barbeque (food options are seriously limited in this area), we wandered into one of the few shops that were still open, where a husband and wife team were handmaking teapots. They were clearly excited by the sight of a foreigner (not an unusual occurrence) and waved us in. We were a bit hungry, but didn’t want to pass up the chance to chat and learn something if we could. As they both worked away, we began peppering in the questions we’ve been asking just about everyone. On at least 2 of these questions they simultaneously gave conflicting responses. This could have been due to seemingly genuine excitement, or the fact that they weren’t on the same page about what type of potential customer we were. Nonetheless, they contributed to our growing collection of responses.

Only a small portion of sellers and makers were frank about the situation in Yixing. They stated what we already more or less knew, but that most other salespeople shied away from saying – that most modern pots are never pure original mine or scarce clays, and that in many cases they’re blended with outside clays or worse yet dyed. Most of them repeated the same saying when discussing clay: 一分钱一分货. Literally “one part money, one part goods” or “you get what you pay for”.

Unfortunately, you can’t be there when the backhoe digs out the ore from the mountain – especially if that mine was closed over a decade ago. You also probably won’t be able to sit with the clay as it ages for years before being used, or be allowed to watch it be processed. It’s quite likely that you can visit a shop and see a teapot being handmade or half-handmade though. And while fun and fascinating to watch, you have no way of proving what that pot is made of.

These candid individuals also indicated that some claims are quite loose, depending on who you ask. “Original mine” can often just refer to clay from the same mountain range (山脉) in Yixing, which is, you know, close enough, right? Again, it’s easy to draw parallels with the puer scene, in which “close enough” is often sufficient for many sellers to pass off imitation Laobanzhang, Bingdao, Guafengzhai, etc as the real deal. Is it bad tea? Is it bad clay? No, not necessarily, but it’s also not entirely truthful.

So where does that leave you after you’ve walked into a dozen shops and held “original mine zhuni” teapots that cost anywhere from $50 to $30 000 USD? Probably stuck in the middle, hoping. It’s likely safe to use that price range as a scale for certainty, although nothing can be proven, no matter what the cost of the pot. The adage holds weight, that if it’s too good to be true, it probably is.

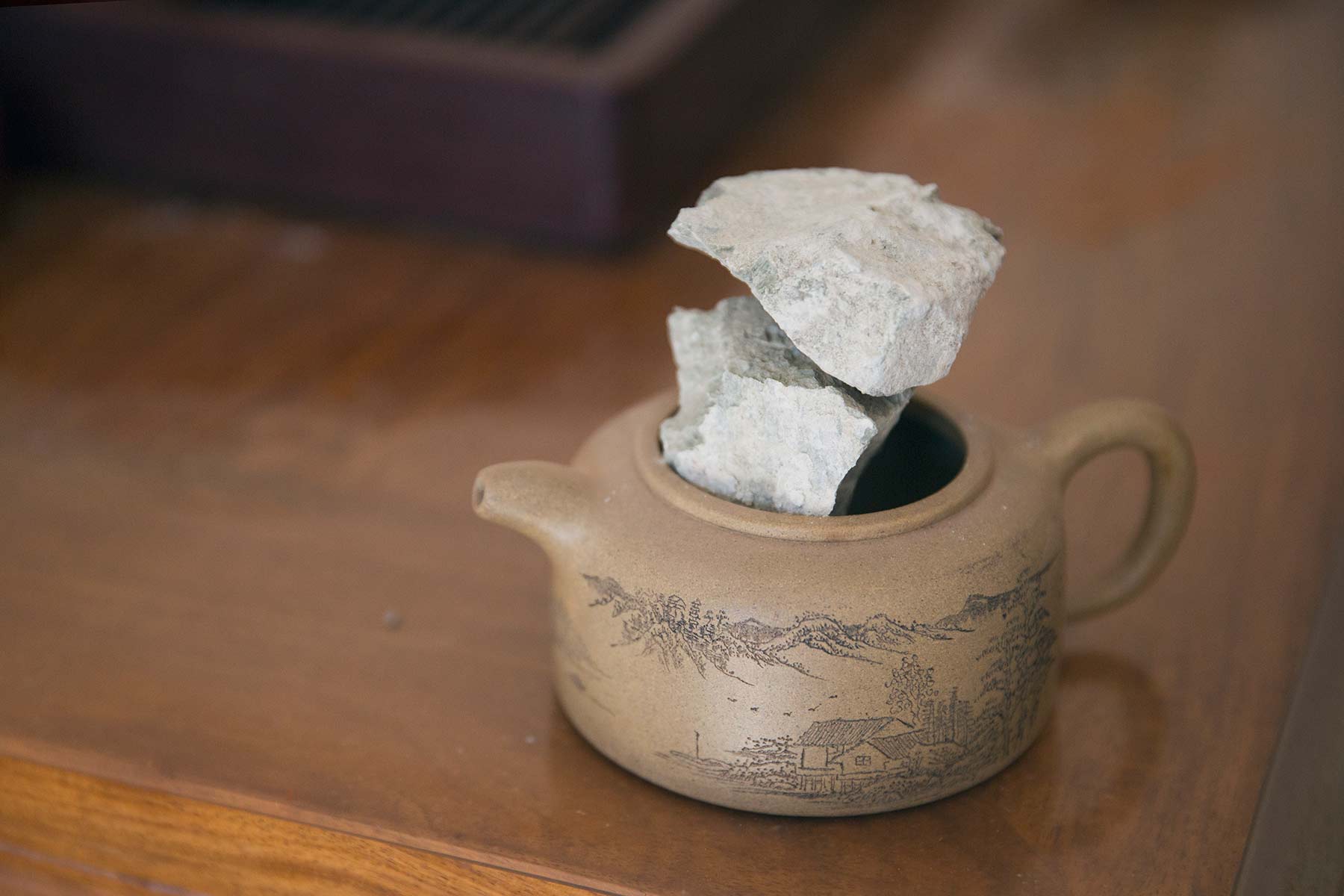

One comment that someone made while driving with us stood out. As we passed courtyard close to the the #4 mine at Huanglongshan, he pointed over to the several large piles of what looked like zini and hongni in the center, all locked behind a large gate and security. “Huanglongshan,” he said, referring to where it was mined. He then indicated that around 15kg of that raw ore alone would cost ¥10 000-15 000 from that particular source. His response when asking who the buyers of this clay are was “the masters”. Whether that’s the going rate, a high or a low estimate, it still emphasizes the value of true Huanglongshan clay. From there it still has to be processed, which will add its own cost. To bring back the tea-clay comparison one more time, at least an in-demand tea’s availability can be justified by the fact that it is harvested one or more times a year. Clay, on the other hand, doesn’t grow on trees.

Read the thrilling end to this saga in Part III.

In part III we will go into more detail on the various types of teapots (fully handmade, half-handmade, slipcast), the work that goes into them and the value, so please check back soon.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.