Four Days in Yiwu

As this is our first blog post, I suppose an appropriate place to start is with how we got into tea. Currently we are in the process of planning our next trip to Yunnan’s main tea growing region at the end of the month, so I think it’s relevant to reflect on our first trip to Xishuangbanna that started it all, just over a year ago in 2014.

After living in Yunnan, China for several month, my wife Coomi finally was able to push her father to arrange a trip down to meet a tea farmer and close friend of his in Yiwu. Coomi’s father has been both drinking puer tea and travelling all over Yunnan for many years. Thanks to his experience and contacts, we were fortunate enough to get such a warm reception there.

For geographical reference, Yiwu is one of the six great tea mountains in Yunnan and is located in the south corner of Yunnan, adjacent to Laos. It lies in the Dai autonomous prefecture of Yunnan, which has a lot of great reasons to visit besides tea, such as food, temples, biodiversity, culture, more food, etc.

It’s almost impossible to live in Yunnan and not be familiar with puer tea, let alone have tried it, but for us it was the first-hand experience of seeing how the tea is processed, from pluck to press, that really drew us in. After wandering through tea fields, watching the tea be roasted and drinking with people who have devoted their life to the craft of making tea, it would have been hard to go back to just casually drinking tea. The process and history of puer tea is a particular fascinating one, and not very commonly known in the western world.

So what’s it like getting to Yiwu? First, it’s nauseating. You will have to spend a lot of time sharing roads no bigger than 1.5 lanes with opposing traffic that consists of trucks, scooters, cars and pedestrians. After that though, it’s quite a peaceful place, at least the stretch we were at. The first person we encountered was Ms Li’s 91 year old grandmother, rolling some leaves just before the last drying process. We passed by some leaves spread over a bamboo mat to dry in the sun and proceeded inside to drink some tea. At this point we learned more about her own background and history with tea.

A few years younger than us, she is a relatively young farmers, carrying on her family’s trade. While her family background has laid a foundation for her to build her expertise and develop her business, it has not spared her from shouldering a massive workload in order to ensure she’s producing quality tea. Over time, some processes have become smoother, but she still oversees and maintains close involvement in every aspect of production. Even as we were saying goodbye we were driving with her into town so that she could choose packaging.

The primary reason that her workload is so large is trust, unfortunately. One aspect of this is trusting her workers. Yiwu’s tea has some very noticeable properties and demand has increased over the years, also increasing the price considerably. Thanks to a highly valued raw product, she often has to keep a close eye on some of the workers picking her leaves. After that, attention needs to be paid to how the tea is being processed. This may be even more crucial to a tea’s quality and reputation than the raw material. Ms Li told us that the most difficult aspect is to find roasters. Roasters will possess a specialized, honed skill, so good ones will be in high demand and therefore difficult to keep in one place as other farmers lure them away with more money.

Lastly, it also requires work to maintain other people’s trust in her tea. During an era where puer tea’s value has shot up and people have had dollar signs in their eyes, Ms Li stressed the importance to sticking to your own vision and principles. Many farmers unscrupulously cut corners, embellish or even flat out lie about their products. China has an unfortunate reputation for forgery and corner cutting, which I try not to dwell on too much, but it also must be acknowledged, especially in the difficult-to-verify tea world. I would say mutual trust between farmer and buyer (and so on down the line) is paramount in the world of puer tea.

When we went out to see the first of the tea fields, we able to bear witness to one of the most exaggerated and falsified types of puer tea: ancient tree tea. Despite what you might believe by seeing the number of puer tea labels that have the words “ancient tree” written on them, there are not actually a lot of true ancient trees in Yiwu. Additionally, the term “ancient tree” is not attached to a specific numeric age, so even in legitimate cases, its application can be very loose. There are certainly some, but you will find more “qiao mu”, which refers to the non-shrub, trunk-having, non-manicured variety of tea tree (arbor). Unfortunately false and exaggerated tree ages are fairly common on all puer labels, not just those from Yiwu. Thanks to the reputation of Yiwu teas, even some claims of Yiwu as an origin are exaggerated or falsified.

The next day we went from neighbor to neighbor, drinking and talking tea. As we were visiting during the summer, everyone had a little more extra time to spend with us than if it were spring. Although these were probably atypical days for them, I could see getting into the lifestyle of raising tea. We also noticed a marked difference between each farmer’s tea. Even though the tea was all grown within a close proximity, they all had very unique characteristics. Being in the tropics, there was no shortage of delicious fresh fruit to eat as we drank, often also grown by the tea farmer we were visiting for personal consumption. These included fresh green mangos, homegrown mini-bananas, lychees, mangosteen, pineapple, etc. Another good reason to live on a tea mountain.

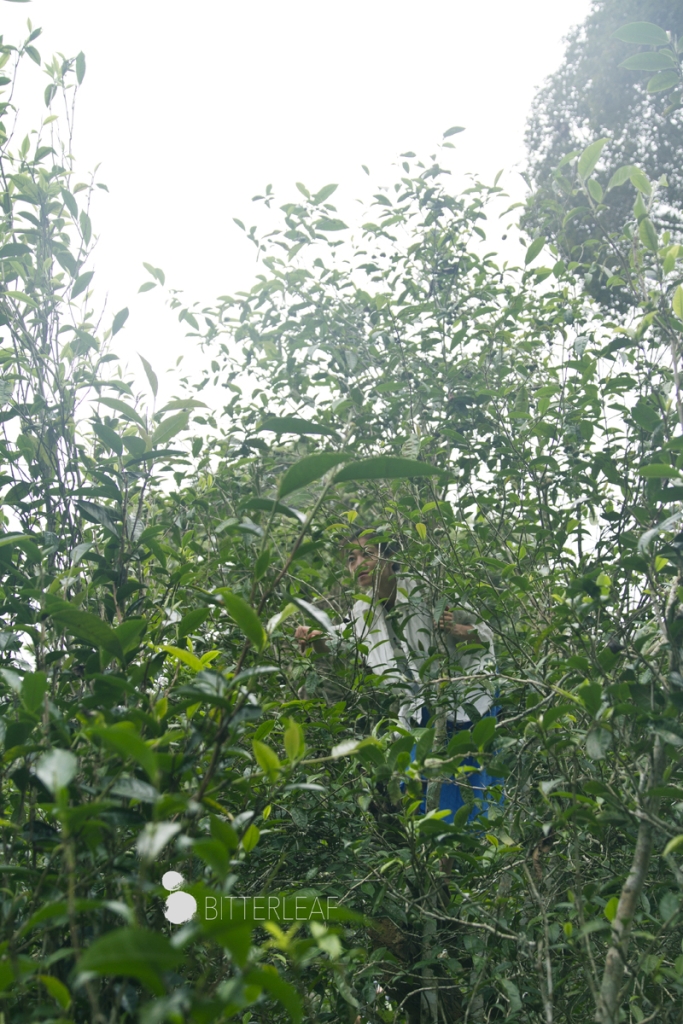

In the afternoon we visited a friend’s (supposed) organic tea garden. The typical image of a tea garden is rows of low, uniform bushes on a gentle slope. This “garden” was more like a mountainside jungle. The tree placement obviously hadn’t been planned, as there were no organized rows. We were constantly reminded that this was an organic plot as we brushed spider webs off our faces and batted away other random insects. Another feature of this garden was two giant lychee trees in the center of it. The presence of this tree apparently gives a unique flavor to the tea that surrounds it. The work in the garden certainly didn’t look easy. As these are “wild” trees, they had grown considerably higher than the terrace style tea bushes you commonly see along roadsides. Attention also has to be paid to how the leaves are picked in terms of the number of leaves and ratio of leaf to bud. Ms Li noted that she is always in need of people to pick tea in the spring and jokingly suggested we come then to work in the field, although I think she was also partly serious.

Picking the tea is only half the battle. Back in the village people were working well into the night to process the tea and prepare it for pressing. Puer tea first has to wilt by sitting out for a few hours. After this the leaves are lightly roasted to “kill the green” and prevent the tea from oxidizing (the process by which black tea is made) too much. After being lightly roasted, the leaves will be lightly rolled (bruised) and then left in the sun to be dried, sorted and eventually pressed into cakes, bricks, or whatever other shape they’re destined for. This is the process for raw puer. In a few words, ripe (fermented) puer involves an additional process of leaving the tea in damp piles for several weeks or even months. This accelerates the fermentation process that raw puer naturally undergoes over several decades, but it’s not something you’ll typically witness in small villages or with highly valued raw materials. More on ripe tea another time.

We watched the process of raw puer, and while they seem simple enough in theory, the quality of a puer depends as much on the skill of the producer as it does on the qualities of the tea leaves. You could have the oldest, most organic, sacred, expensive material completely botched by a lengthy roasting process. This throws another wrench into the system of judging puer by its cover. Even if the label’s claims about tree age and origin are accurate, the skill of the processor can produce lackluster results. While we watched the workers processing the day’s batch of tea, Ms Li watched even closer.

The rest of our time in Yiwu was spent drinking tea, eating meals made from various reptiles, and drinking some homemade baijiu (Chinese rice liquor), which luckily did not harm my 20-20 vision (nor Coomi’s not-so 20-20 eyesight). Over these few days our knowledge about tea multiplied several times, but that was just the beginning. As we drank with Ms Li , she modestly described herself as “still learning”. I found this incredible coming from someone who can with a relatively high level of accuracy determine not just which mountain, but the patch of land a tea comes from with just a blind tasting. Even with a family background in tea and over 10 years’ experience independently producing her own tea, she still recognizes that she will be learning all of her life.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.